HARD PASSAGE By Pierre Beemans (Book Review)

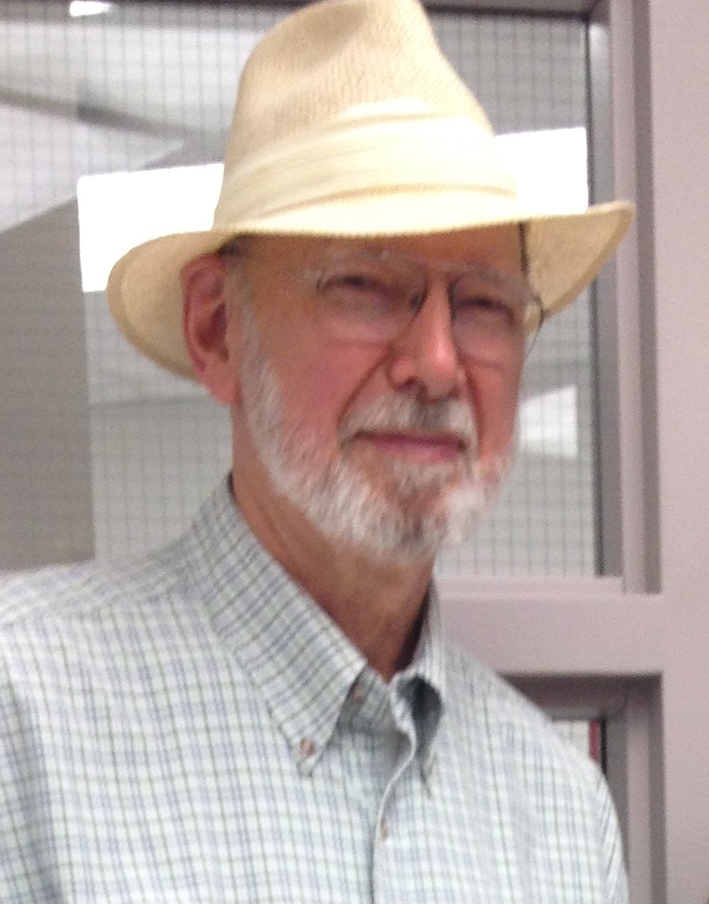

Pierre Beemans

Hard Passage, by Arthur Kroeger

University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, 2007. 269 pp.

There are several good reasons to head down to the library (or the bookstore) to pick up a copy of this book, especially if you are a former civil servant in Ottawa.

Subtitled A Mennonite Family’s Long Journey from Russia to Canada’, at the most basic level it chronicles exactly that: the peaceful and relatively prosperous Southern Russian Mennonite colony into which Arthur Kroeger’s father and mother were born towards the end of the 19th century, their courtship and the start of their family at the start of the 20th century, the upheavals occasioned by WWI, the Bolshevik Revolution and the Russian civil war, the flight of the Kroegers and thousands of other Mennonites to Canada as penniless refugees in the 1920s, their struggle to survive and adapt in as subsistence farmers in the dustbowl of Southern Alberta, and the success that eventually crowned their efforts as parents and children worked their way out of poverty into mainstream Canadian society.

The book is much more than a Kroeger family biography, however. What little I knew of the Mennonites was that they were prosperous farmers in Western Canada and Southwestern Ontario who stuck together, had good food, and shared their bounty generously with developing countries through the work of the Mennonite Central Committee. Kroeger’s description of the religious and historical movements that brought the followers of Menno Simon from the Low Countries in the 16th c. to Poland in the 17th c. to the lower reaches of the Dnieper River at the end of the 18th c., and of the communal and religious culture of this hard-working, devout and pacificist people was in itself worth the read. I knew from my own studies of the cataclysmic events that followed the start of the First World War, and the savagery of the roving armies of Reds, Whites and warlords during the civil war that followed the 1917 Revolution, but seeing how these were experienced by simple and helpless rural farm people -- as recorded in the journals of Heinrich Koeger and other Mennonites -- gives a new dimension to the horrors of that period.

The second good reason for reading Hard Passage lies in its unsentimental account of the hardships that settler families endured in the first few decades of the last century, especially in land that was never suitable for farming, like the Palliser Triangle. The Mennonite refugees faced some obstacles that were particular to their situation, including the debt they had to repay for their passage from Russia, but the Kroeger family is shown as an exemplar of what thousands of other farmers across the West lived through in the drought of the Twenties and the Depression of the Thirties.

For those of us who grew up in the post-WWII economic boom (let alone for our children who grew up in the affluence of post-60’s consumer society), it is hard to imagine the world our parents and grandparents lived in before Old Age Security, Medicare, Employment Insurance, the Canada Pension Plan, public welfare and social housing, if they were not in the middle class and especially if they were not native-born Canadians. I would recommend to many of us that we sit down with our children or grandchildren some evening and read aloud to them chapters 7-13 of this book, with titles like Boiled Apple Peels’ and Russian Thistle (tumbleweed, to the the non-Albertan) and Relief’.

Thirdly, there are some parallels between the attitudes displayed towards immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe (let alone from China or India) from the 1890s through the 1930s by many officials and politicians and by a large segment of the British-stock Canadian public, and the attitudes one sometimes hears and reads about today concerning the influx of newcomers from the Middle East, the Caribbean, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa: “they don’t share our culture, they don’t speak our language, their religion is alien to our values, etc.” or “immigrants, yes, but not too many and only the ones with the skills our economy needs”. I was unaware that the Borden government had passed an Order-in-Council in 1919 barring the entry of Mennonites (repealed by MacKenzie King in 1922), and on the other hand, that it was Sir Edward Beatty and Colonel John Dennis of the Canadian Pacific Railway who went out on a long limb to bankroll the inflow of 20,000 Mennonites from Russia between 1923-30, swallowing much of what would amount to over $100 million in today’s dollars.

Kroeger’s book reminds us that, within the short space of 40-50 years, immigrant children who went to school barefoot while their mothers washed floors in public buildings and cooked meager meals from welfare packages went on to become prominent businessmen, cabinet ministers and federal mandarins (Kroeger and his brothers fill out all three categories) and just good, hard-working tax-paying citizens. This is a book that should make Canadians feel good about what this country and its people have grown through, and feel confident about what the future holds for our children and those who continue to join the adventure that is Canada.

The last chapter hurries through what has become of the Kroeger children since the family finally got its nose above water in the 1940s. This may just be modesty on the author’s part, or perhaps he was feeling rushed to finish the book. Although the second half focuses on the Kroeger family and their life in Alberta, I think it would have benefitted if he had added a chapter outlining the other parts of the Mennonite experience in Canada: the movement of Swiss Mennonites into Ontario in the early 19th c., how the first Russian Mennonites came here in the 1870s, the development of the Mennonite coops in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and the different branches of Mennonitism.

I never dealt with Arthur Kroeger during my years in the public service, but I was well aware of the reputation he enjoyed as one of the finest mandarins in Ottawa. Although he never intended it thus, this book is a tribute to the man and to the values his parents passed on to him -- no doubt someone else some day will write his biography. His story would certainly come as a surprise to those who think of public servants as colourless suits’ pushing paper in drab offices.

Tags: Pierre Beemans